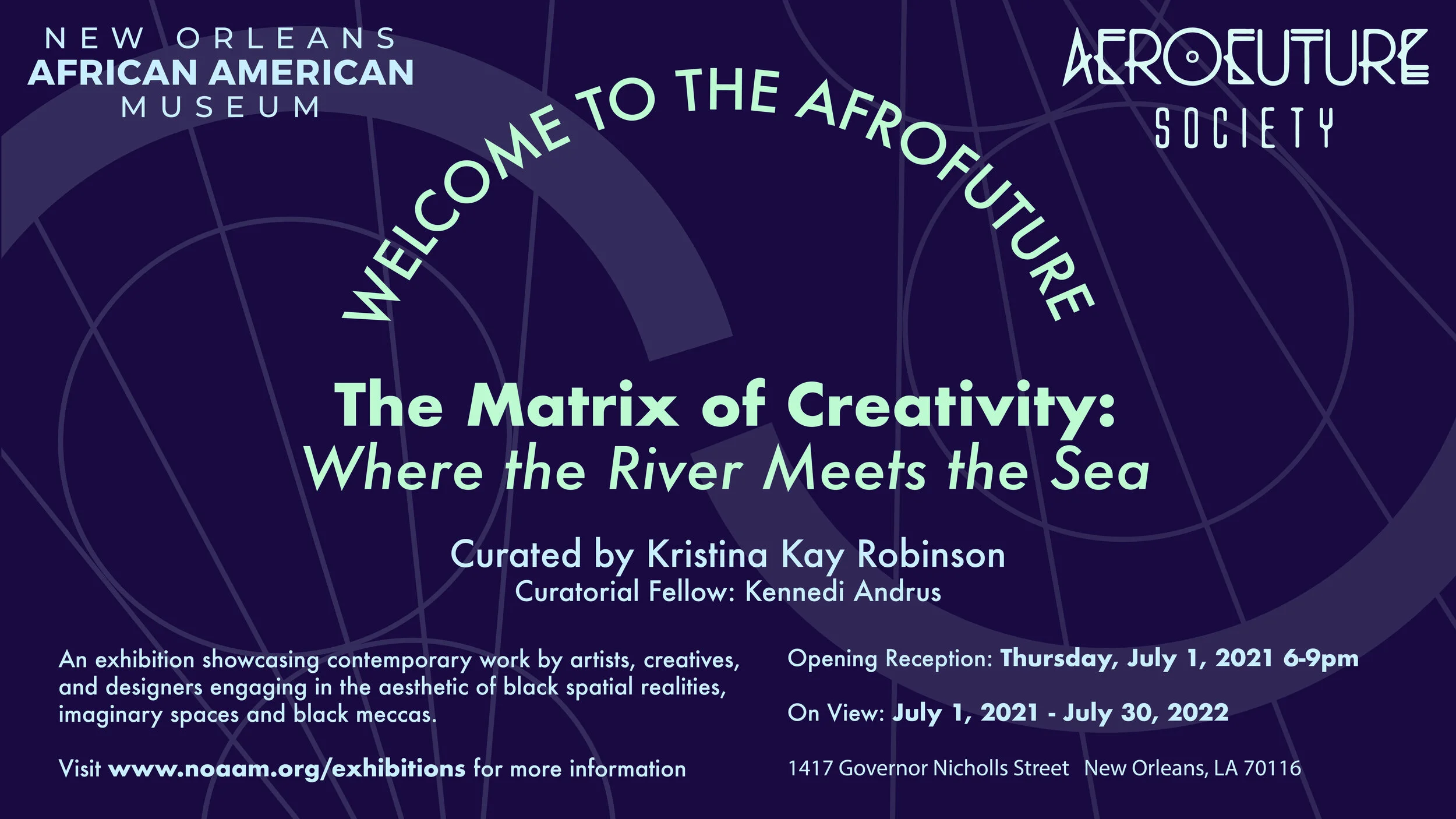

Welcome to the Afrofuture:

The Matrix of Creativity: Where the River Meets the Sea

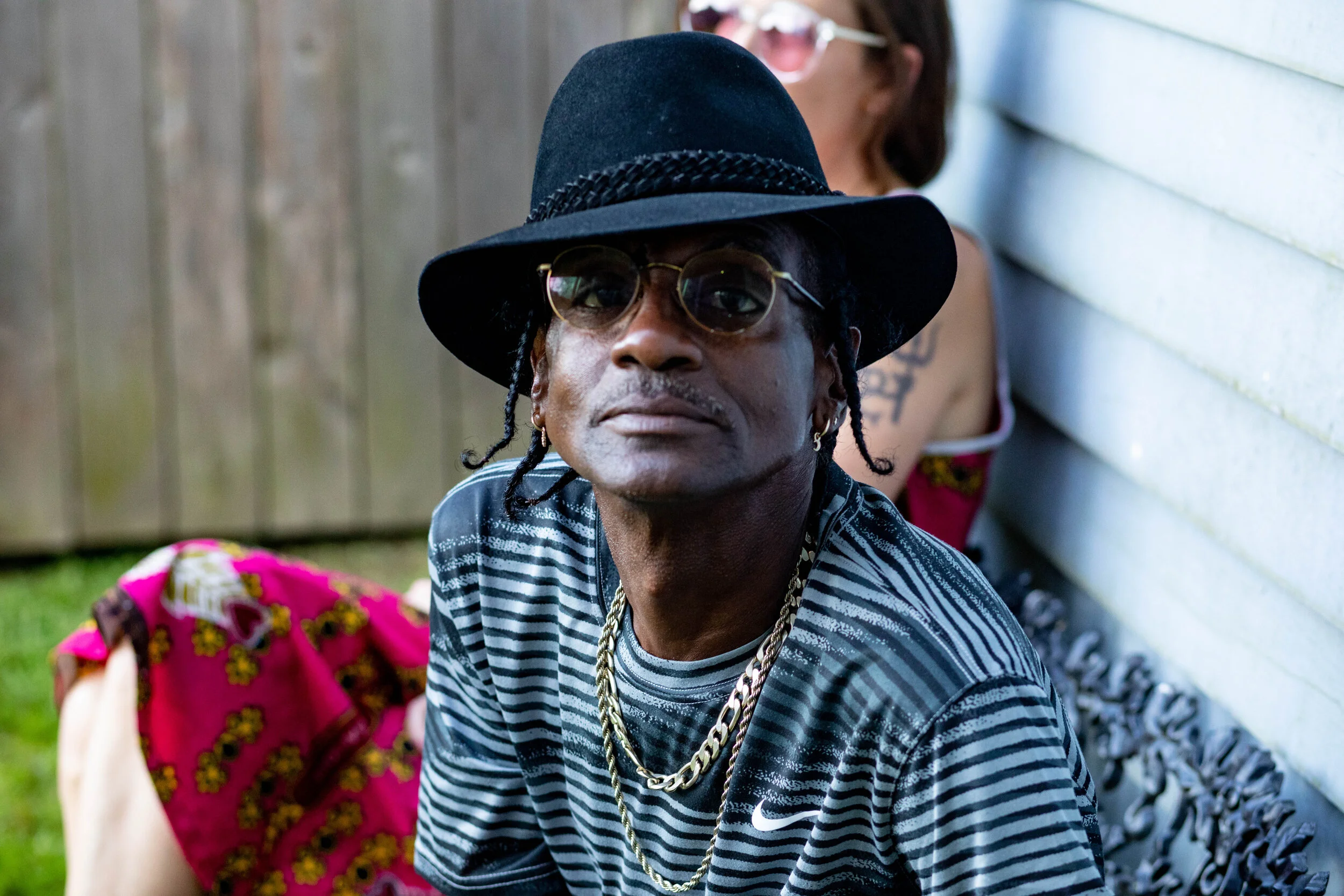

photos from the exhibition opening on July 1, 2021 by CFreedom Photography

An annual exhibition showcasing contemporary work by artists, creatives, and designers engaging in the aesthetic of black spatial realities, imaginary spaces and black meccas.

July 1, 2021 - July 30, 2022

Featuring:

Khalid Abdelrahman, Langston Allston, Kennedi Andrus, Dianne “Mimi” Baquet, Didier Civil, Rodrecas Davis, Eseosa Edebiri, Sokari Ekine, Ashley Firstley, Myesha Francis, Jacq Francois, Cherice Harrison-Nelson, Cheryiah Hill, Tatiana Kitchen, Soraya Jean Louis, Gael Jean Louis, Lance Minto-Strouse, Steven Montinar, John Jahni Moore, Jameel Paulin, Schetauna Powell, Nik Richard, Ryann Sterling, Khalid Thompson, Bianca Walker, Sly Watts

In a 1986 interview with Dr. Jerry Ward Jr. New Orleans writer and griot, Tom Dent characterizes New Orleans as a “matrix for creativity.” The fugitive praxis of syncretism ( the combination of different religions or religious traditions into a new form) manifests throughout the continuum of this land’s history from the pre-colonial Mobilian trading language created by the numerous nations indigenous to this estuary, the Kouri Vini (Louisiana Creole) spoken by the descendants of enslaved Africans and Natives, to the spiritual invention of New Orleans gris gris and in the sound of brass, jazz, and bounce music.

The cosmology of the Bambara, a Mandé people, who made up a larger portion of the enslaved population in Louisiana than anywhere else in the Western Hemisphere, is described in some detail in Gwendolyn Midlo Hall’s Africans in Colonial Louisiana. “According to this cosmology, the universe, emerging from a moving void, undergoes a slow process of acquiring voice and vibration that eventually evolves into light, sound, creatures, actions, and human sentiments. The order of this universe is expressed arithmetically through numbers one through seven, as is outlined in Cheikh Anta Diop’s, Civilization or Barbarism. Native to Mali and later stolen from the Senegambia region, the Bambara’s cosmology is designed to be transported across distance.

In Flash of the Spirit, Robert Farris Thompson examines the word Mandekan word woron. Meaning to “get the kernel,” it encapsulates the process needed to master speech, song, music, or any aesthetic endeavor. Thompson goes on to outline the Mandé concept of reason, which relies on a balance of opposites, badenya (the conformist) and fadenya (the innovator). It is this tension between tradition and innovation that produces a culture always in flux, always moving, changing, and reinventing the world.

For example: the five hundred Black rebels in 1811 of various ethnicity, who envisioned a free New Orleans, a free Louisiana, and an America free from slavery or the Natchez and Bambara nations, who just ten years after the Louisiana colony’s establishment, conspired together to overturn it. It is both the retention of key African cultural concepts and the space and ability to innovate in New Orleans that makes the city the perpetual site of what’s new and next on the horizon. As such, The Matrix of Creativity : Where the River Meets the Sea holds space for both traditional and new interpretations of who and what kinds of figuration, abstraction and narrative constitutes the work, history, and legacy of Afrofuturism.

Curator in Residence, Kristina Kay Robinson

The term Afrofuturism has taken on thousands of interpretations across the African diaspora by visual artists, writers, filmmakers, vocalists, dancers, philosophers, and thinkers. The philosophy of Afrofuturism itself has broad understanding, as it encompasses images created by thinkers throughout the diaspora, who take on the challenge of imagining innovative futures centered around themselves in a present that has not yet known equitable artistic spaces for black people. The term itself was coined by Mark Dery, a white author who writes of Afrofuturism as an imagined future through the lens of African Americans, heavily influenced by and based in current technology and the possibilities it presents for the future. He asks the question, is it possible to imagine a future as a part of a community whose own history has been hidden, erased, and infringed upon? Is it possible for those imagined futures to exist outside of the reality we have had access to?

As black people continue to explore these futures, it is necessary to acknowledge the existence of afrofuturism outside of the use of technologies that are typically used to define society’s progress. Artists of the African diaspora hold a unique position in the realm of creativity, one where the act of creating with the intent to reach the public is radical in itself. Imagining a future where there will be space for the work of black creators while creating said work, poses a dilemma for the black artist that itself takes introspection and imagination to navigate. In this sense, Afrofuturism and the ideas it encompasses can be further explored by all artists existing in the diaspora in spaces where their work must go through the hurdles of inequality, alongside the act of creation itself. The Matrix of Creativity: Where the River Meets the Sea works to explore these possibilities of alternative interpretations by inviting new ideas of Afrofuturism in visual art and the work that emerges from them.